by Ken Masugi

Recently, the Heritage Foundation and the Scalia School of Law at George Mason University honored Justice Clarence Thomas on the 30th anniversary of his joining the Supreme Court. A day of panels featuring former Thomas clerks and prominent legal scholars commented on his legacy and future. The justice responded that evening.

Yet even a full day of often enlightening panels and speeches, doubtless to be supplemented in the years to come by law review issues, articles, and books, misses the crucial fact about Thomas’ jurisprudence that has made him the indispensable justice: his overarching focus on natural law.

In America natural law comes to sight in the principle of equality, which continues to confuse both conservatives and liberals. With the Democrats’ embrace of “equity,” they have cast aside equality as a principle. Conservatives have never been comfortable with equality to begin with, as Harry Jaffa consistently pointed out in his work. Equality does not mean socialism but rather government by consent, and all the institutions that follow from the preservation of this fundamental element of justice. The clearest expositor of this principle, as Thomas explains, has been Abraham Lincoln, when he attacked the evil of slavery.

The aftermath of the Civil War undermined the political attractiveness of equality for both Left and Right, for different reasons. The Left was further cut off from equality by Woodrow Wilson’s attack on the Declaration, the Right by the hyperpartisanship of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the endless quest for security.

Transcending this muddle over equality arose Clarence Thomas, who produced some remarkable writings on natural law and equality. Those who come up clueless—some perhaps disappointed, others perhaps relieved—at not finding a Thomas Aquinas emoji in his writings, need the counsel of former clerk John Yoo, who spelled out the importance of natural law to Thomas clearly:

While the principle of natural rights may sit silently beneath the crashing waves of the latest disputes at the Supreme Court, whether over abortion, the right to bear arms, or affirmative action, do not doubt that it is there. Justice Thomas made this clear in a remarkable speech delivered in September at the University of Notre Dame for its Alexis de Tocqueville series . . . That Justice Thomas has been able to dedicate himself to the unfinished work of the Declaration of Independence, and to set an example for others to take up that work, is the very fulfillment of that document’s promise. His coming years on the Court will reveal how his belief in natural rights may fare against the centralized government, identity politics, and critical theories of our own day.

Yoo does not need to torture any of Thomas’ writings to expose renditioned natural law closeted beneath. Quite the contrary, we see in his Notre Dame speech (whose rough transcript I edit slightly for accuracy):

But despite [segregation and Jim Crow] there was a deep and abiding love for our country, and a firm desire to have the rights and responsibilities of full citizenship. Regardless of how society treated us, there was never any doubt that we were equally entitled to claim the promise of America as our birthright, and equally duty bound to honor and defend her to the best of our ability. We held these ideals first and foremost, because we were raised to know that as children of God, we were inherently equal and equally responsible for our actions . . ..

Whether deemed inferior by the crudest bigots [or] considered a victim by the most educated elites, being dismissed as anything other than inherently equal is still at bottom, a reduction of our human worth. My nuns at St. Benedict’s taught me that that was a lie. And to paraphrase Solzhenitsyn, we were not to live by that lie. [I]n God’s eyes, we were inherently equal, and that was the truth that permeated our home life as well—less with a focus on rights and more with a focus on what was required of us as children of God. [emphasis added]

These are all key natural law principles: you have a duty to love the country you’re born into and seek within it what is true and elevating. You exercise your natural rights, such as acquisition of property and self-defense, but you remain at peace with your fellow humans. Various inconveniences oblige you to leave the state of nature, but this is done deliberately. This Catholic teaching bore further fruit in later years:

I use this background to set the stage for my later and more in depth encounter with the Declaration of Independence in the mid-1980s. At that time, having run agencies and seeing how the federal government actually worked, I became deeply interested in The Declaration of Independence. I had hoped studying the founding would bring some clarity to the cacophonous world in which I found myself. Yet, studying the founding . . . [was] more like a return to familiar ground, the ground of my upbringing.

The Declaration captured what I had been taught to venerate as a child, but had cynically rejected as a young man. All men are created equal, endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights. And so . . . the Declaration of Independence did not propose to have discovered anything new. Its truths were self-evident. They were beyond dispute. They were a priori in the society of my youth, and by the school, [at] home, and in the culture they were given. And, as I rediscovered the God-given principles of the Declaration and our founding, I eventually returned to the church, which had been teaching the same truths for millennia. That the Declaration set forth self-evident truths was no accident.

The Declaration, as with other natural law documents for men and women throughout the ages, brought Thomas back to God. While it may not have that power with others, this synthesis of reason and revelation must be respected.

As Thomas wrote in his autobiography, reflecting on his pre-judicial government service as Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

I led my staffers (especially Ken Masugi and John Marini) in discussions of the natural-law philosophy with which the Declaration of Independence, America’s first founding document, is permeated. ‘All men are created equal,’ Thomas Jefferson had written in 1776 ‘They are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.’ That’s natural law in a nutshell: if all men are created equal, then no man can own another man, and we can only be governed by our consent.

Men exist between God and the beasts, as both the Declaration and Psalm 8 make clear. Political life, the City of Man, subsists outside the City of God. This limit on the legitimate authority of government meant that man’s freedom had to be respected. Unlike Barack Obama, who made “equality” an excuse for unlimited government authority for unlimited purposes, Thomas’ equality maximizes individual freedom, but a freedom based on natural law principles.

A fine example of Thomas’ use of natural rights goes back almost 35 years ago. In a November 21 1986 letter to the Wall Street Journal titled “‘Natural Disgust’ and Natural Rights,” Thomas, who was chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission at the time, raised the issue of how we Americans came to recognize and eventually enforce natural right, in abolishing slavery. In denouncing the Dred Scott decision, which cut America off from its natural right founding principle, Lincoln responded to Douglas’ demagogic charge that “Black Republicans” wanted to have a promiscuous society of mixing races. Of course Douglas suppressed the key point that black slaves, men as well as women, were exploited, both sexually and economically, and often brutally.

Rather than declining to address the “natural disgust” that Douglas threw in Lincoln’s face and that most Americans accepted as following from slavery, Lincoln, Thomas noted, sought to teach Americans about the injustice of this undeniable evil.

Lincoln showed how “natural right,” or fundamental justice, would lead Americans out of the disgusting horror Douglas depicts (and whose cause he distorts). Lincoln says bluntly that the force of Douglas’ argument is because “I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. I need not have her for either.” (A condition, I should note, which holds for a black man as well.) “I can just leave her alone.” Lincoln concludes, “In some respects she certainly is not my equal”—which logically means that she may also be Lincoln’s superior in some respects—“but in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands, without asking leave of any one else, she is my equal and the equal of all others.”

The work ethic, honored and respected by northern and western men and women, though at that time losing its hold in the South, had at its core this principle of natural right to acquire and benefit from ownership of property and labor with it. And property included one’s mental and spiritual qualities, as well as physical possessions. Justice can moderate passion. It can create the conditions for civility and even friendship. Natural right can redirect and transcend natural disgust.

Sometimes such an instinctive disgust can also be instructive about natural law. In an exchange with Senator Howard Metzenbaum, which Thomas recounts in his autobiography, he explains, “all I did was ask him if he would consider having a human being sandwich for lunch instead of, say, a turkey sandwich. That’s Natural Law 101: all law is based on some sense of moral principles and human purposes inherent in the nature of human beings . . ..”

There is no magic trick that can create political virtue or even simple sanity in Washington, D.C., where too much power and control over wealth has caused our political class to self-aggrandize for well over a century. But is this really a country where “gender fluidity” is gaining acceptance? Even if it is, Natural Law 101, expounded by the jurisprudence of Clarence Thomas, would be a powerful argument on behalf of justice and a proper reordering of our country, as it lumbers along toward its 250th birthday. This Thomas testament would be the new Gettysburg Address for our battles today.

– – –

Ken Masugi, Ph.D., is a distinguished fellow of the Center for American Greatness and a senior fellow of the Claremont Institute. He has been a speechwriter for two cabinet members, and a special assistant for Clarence Thomas when he was chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Masugi is co-author, editor, or co-editor of 10 books on American politics. He has taught at the U.S. Air Force Academy, where he was Olin Distinguished Visiting Professor; James Madison College of Michigan State University; the Ashbrook Center of Ashland University; and Princeton University.

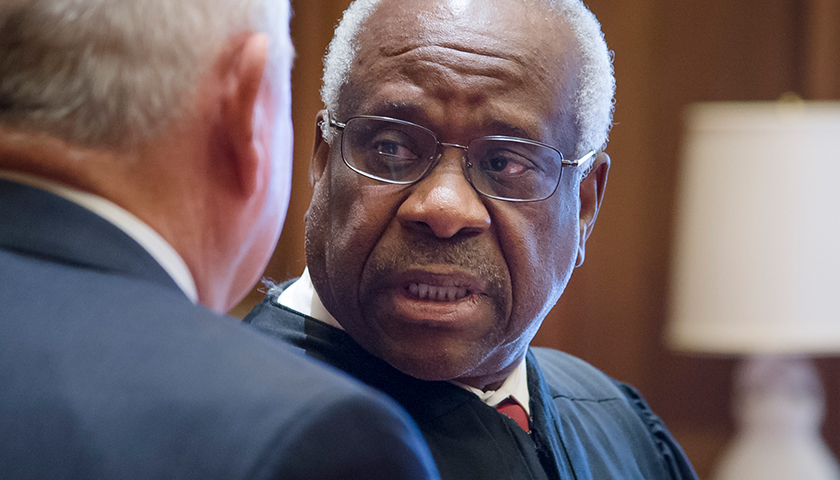

Photo “Justice Clarence Thomas” by Justice Clarence Thomas.